Editor’s note: This article was originally written on the 10th anniversary of the Oklahoma City Bombing and was published with the author’s permission.

There is not much to be said about the Oklahoma City federal building bombing that has not already been said. It has been 10 years since a Ryder truck packed with a fertilizer and fuel bomb tore through that building and forever altered the physical and psychological landscape of my hometown. The ensuing years have seen Oklahoma and the nation endure more than I ever would have dreamed possible before April 19, 1995.

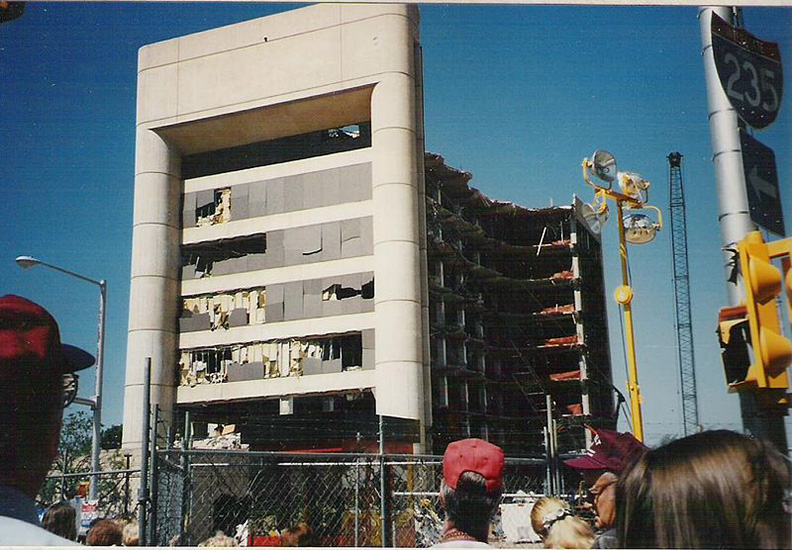

I was a journalist at the time, and I vividly remember the moment I saw the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building’s shattered frame in person, some 45 minutes after the explosion, thinking to myself that I’d likely never witness again anything so horrific in my state — or my country, for that matter. And then six years later, the 9/11 attacks would dwarf the Oklahoma City tragedy with a death count more than 17 times the 168 victims of the federal building bombing.

In many respects, the bombing was the defining moment in my life. For more than three years, it consumed me professionally, to the point of obsession, really. It impacted relationships, leading to friendships and the dissolution of others. It connected me to my native state in a way I wouldn’t have thought possible. It drew me into situations and brought me to people who continue to haunt me. And there are moments from that day and the weeks and months that followed I will never forget.

I remember the second false bomb scare to occur that morning. The first was around 9:30 a.m., which sent rescue workers, reporters, police and onlookers fleeing for their lives. I had missed that scare by about 15 minutes, but when the second false alarm arrived, around 11 a.m., I was caught up in a stampede north of the bombed-out Murrah site. I remember ducking behind a parked car and seeing another reporter, a woman I had worked with for many years, break down sobbing and shaking and repeating, over and over, “I hate this, I hate this, I hate this …”

I remember catching a glimpse of a makeshift triage, a cluster of lacerated and bloodied and dazed people on the ground, that had been set up in a downtown parking lot near the Murrah building. The area briefly became visible to the media after one of the large trucks hiding it was forced to move. The streets already were thick with walking wounded, people with cut faces and hair matted with blood. The sea of patrol cars and ambulances, some from as far north as Claremore, was extraordinary.

I remember being struck by the magnitude of the impacted area. The Murrah building was Ground Zero for the blast, but downtown Oklahoma City, for about a quarter-mile in all directions, looked as if it had weathered a nuclear attack. The YMCA, the Journal Record Building, the Athenian restaurant, the Oklahoma Water Resources Board Building and a multitude of other structures were in a shambles. Downtown streets glinted from sheets of shattered glass.

I remember interviewing workers in a health clinic that, despite being several blocks north of the bomb site, had lost all its windows and doors in the blast. It was there I heard on a radio that a death count was starting to build for a daycare center that had been inside the Murrah building.

Near Ground Zero, I remember coming across a friend of mine, a paramedic who was among the first to arrive at the scene. And I will never forget this tall, lumbering hulk of a man crying as he recounted how EMTs set up a morgue for the children who had been in the building’s America’s Kids Daycare Center. He described rows of tiny bodies draped by small blankets, all of them stretched out in the shadow of playground equipment at the YMCA.

Sometime that afternoon, rain began to fall. The nearby Civic Center had been transformed into a briefing area for media. It was there I joined other reporters converging upon then-Governor Frank Keating. And it led to a strange epiphany; I had considered myself a cynical and anti-authority contrarian up to that time, but I was almost flat-out ecstatic to see the governor of the state — as if it really meant something. For the first time in my life, I understood the impressive calming effect of leadership, and for the first time that day, I almost felt safe.

I remember two days later, being inside a crowded supply building at Tinker Air Force Base for the initial court appearance of a young man named Timothy McVeigh. He had been picked up by a highway patrolman shortly after the bombing on unrelated charges, but now was the prime suspect in the terrorist attack. Staring at the blank-faced defendant, all I could think was, Christ, what a skinny and gangly and nondescript-looking guy.

I remember crying for the first time toward the end of that awful, exhausting week. It was in my apartment late at night. I was sitting at the breakfast table, transcribing taped interviews from the 19th, when I realized that for most of the tape I had been listening to a constant din of grief: shouting voices, hysterical sobs, police and ambulance sirens and a crush of unmitigated white noise. I began to shake and cry and I did not stop for almost an hour, I think.

And I remember the implosion of the Murrah building the following month, once recovery workers had done all they could. The demolition workers had neglected to do a public countdown, and so the sudden explosion caught many bystanders off-guard and proved particularly frightening for some of the victims’ family members. One older man in particular, whose daughter had died in the bombing and with whom I’d become very friendly, nearly collapsed into sobs.

Oklahomans went on, of course. Many of those impacted by the bombing were never able to get over it, despite the frustrated pleas of many Oklahomans — most, perhaps — who eventually grew exhausted by the never-ending media coverage and suspicious that some were beginning to exploit the tragedy. Many reveled in the details of the subsequent investigation, while others tuned it out completely.

For myself, I will never forget. Nor do I want to.