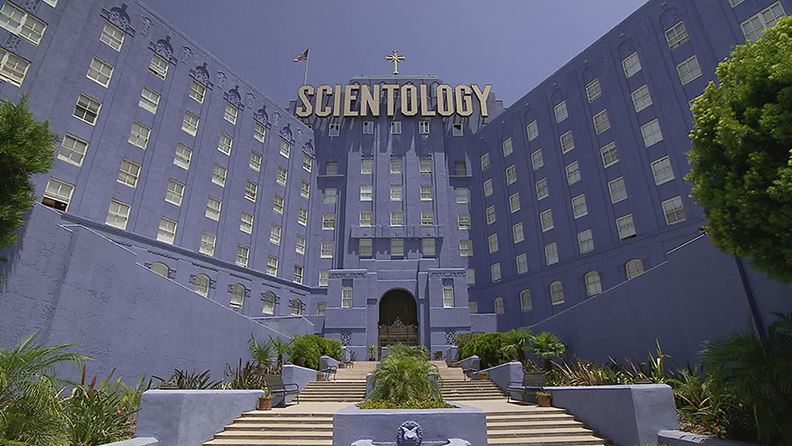

Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief

Director: Alex Gibney

(HBO)

A-

Many documentaries entice with a somewhat masochistic hook. But that’s not to say films like Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s Blackfish or Charles Ferguson’s Inside Job drag about some superficial gimmick or only spark controversy. We don’t watch movies like these to be lulled. We watch them for convenience. We watch them to learn. Most importantly, we watch them to be jarred. We watch them to be violently gouged from a comfort zone, even though we typically are damn sure of what we’re getting into. After all, Googling any ethical issue involving the Church of Scientology will yield innumerable results, and many of us have laughed hysterically at South Park’s “The Return of Chef,” an episode that pokes heavily at the mythological discrepancies Scientology proposes with much parodic accuracy. Even so, Alex Gibney’s Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief manages more of impact than any piece of media examining the phenomenon.

The documentary is obviously informative. Interviews with former members, such as filmmaker Paul Haggis and former Scientology executive Mark Rathbun shed a blinding light on the moral depths to which the organization sunk. Likewise, Sylvia Taylor illuminates the troubles with many of the church’s highest profile members, such as John Travolta and Tom Cruise. The film’s first movement — mostly a biographical discussion about founder L. Ron Hubbard — adeptly describes how in the hell Scientology became such a beast. It also follows the religion’s current leader, David Miscavige, who could easily have an entire film dedicated to his authoritative genre of batshit craziness. There’s a thick list of contextual tidbits that would catch up even the most sheltered viewers on the workings of Scientology, and it does so at a pleasant pace to boot.

Going Clear doesn’t garner any staying power by just being informative, though; it solidifies its weight more naturally, and its editing lends itself to this exponentially. High-motion cutaways are often quick and precise, like its commonly used shot overviewing an auditing machine, a device that attempts to measure thought. Inversely, photographs are presented at crawl, awarding enough time for contemplation and even empathy in some instances. Hubbard isn’t exactly painted in the warmest of colors, but a few of the photographs taken of him – especially when paired with the apt commentary – illustrate an image that leaves you reeling. You could ferret hundreds of reasons why he was a pretty terrible figure overall, but the fact that something as seemingly irrelevant as a brief image could evoke second thoughts is definitely worth noting.

Going Clear‘s cinematography and secondary source use are exceptional. A visual timeline is established relatively early in the work, a notion compounded by well-placed videos and audio excerpts. For instance, recordings from the annual Scientology gala — an event intended to bolster its members’ spiritual liberation — are cleverly sandwiched between comments regarding the church’s dramatically constrictive policies.

Personal tales of peril, loss and persecution from the church’s resigned members are most important to Gibney’s narrative; paternal loss and deprivation appear as sporadically as any of the organization’s nefarious conflict with the IRS, and the snowballing abuse of unadulterated power — especially by Miscavige — is central to the surveillance anxiety pervading the film’s final act. Going Clear never feels more episodic than a traditional film, and religion is ultimately transcended in lieu of an all-encompassing theme (or maybe a more skewed one), propelling the documentary into a class of its own.

Going Clear is 2015’s most essential documentary to date — one sure to encourage a bit of discomfort that should inevitably lead to actualization. But it isn’t simply an attack; it’s a revelatory examination of the power of persuasion, and a dire defense of a healthy humanity.