At first glance, Oklahoma lacks that coastal fertility that a growing film industry needs. Films have obviously taken place here — like William H. Macy’s Rudderless and bits of Terrence Malik’s To the Wonder — but very little of them are truly about Oklahoma. Fritz Kiersch seeks to change that.

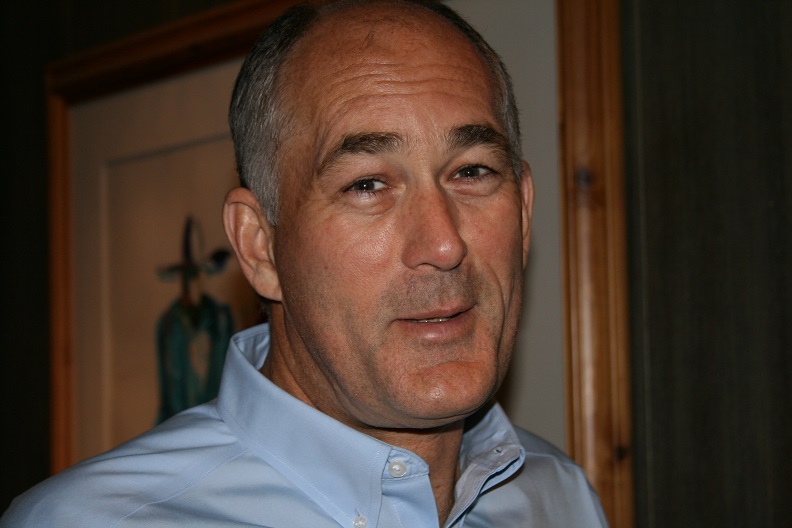

As director of the Moving Images Arts program at Oklahoma City University, Kiersch has immersed himself in the notion of a film-based curriculum since the early 2000s. He directed several films in the decades prior, most notably the original adaptation of Stephen King’s Children of the Corn. Currently, the professor is attempting to get the university’s MFA in screenwriting off the ground.

Kiersch’s initial collegiate pursuit is somewhat unorthodox, given his eventual career.

“Originally, I took a formal education in economics,” Kiersch said. “It introduced me to the core social concepts. However, I’ve always been interested in film.”

In the ’70s, Kiersch made his way to California, snagging a position with Paisley Productions in Los Angeles. There, he quickly flocked to the production side of things, meeting filmmakers while learning the tips of the trade.

As Kiersch would tell you, economics is a far cry from rubbing elbows with the filmmakers of the modern era.

“I soon realized that I was never hired for my degree,” he said. “I was hired because of my passion. It became increasingly important as I got deeper into the business. The people of the industry look at the work you do and determine whether or not it adds value to what they’re doing.”

Late at night, Kiersch would enter his employer’s studio, creating test footage out of the items used for commercials. He ultimately showed his benefactors this work, and though they were initially confused, the soon-to-be filmmaker’s midnight hobby quickly turned into a position as a junior cinematographer.

The Francis Tuttle and Moore Norman Technology Centers currently offer something similar, albeit more kosher. Over the past decade, attendees of these institutes have been awarded opportunities to work with modern recording equipment in a variety of different scenarios, often coming at little or no cost. Kiersch cited the schools as a way for prospective film students to “get their feet wet.”

The development of a film curriculum — let alone an industry — in Oklahoma is at far slower pace than the constant motion of somewhere like LA. Paired with the budding film programs at Oklahoma City Community College, this more lax way of life allowed Kiersch — an industry veteran at this point — to alleviate his eagerness.

“To make a film in California, you really have to focus on a project for about two years,” Kiersch said. “Your output just isn’t very large, and that bothered me. I was more aggressive, and a bit anxious. Through involving myself with the production of student films, however, I could be involved with five different projects at once.”

Years ago, a few individuals cued Kiersch into some developments in the heartland. Several state officials were interested in the economic development of Oklahoman motion pictures. Specifically, how to develop a program at an institution like OCCC.

Kiersch made his move to Oklahoma City around the same time, as the annual deadCENTER film festival took its first shaky steps to becoming the downtown event it is today. Kiersch feels that OCCC’s academic programs, paired with the workshops the aforementioned film festival puts forth, show off what it’s like to become involved at several different levels.

But developing a new film program is never easy.

“These programs have to compete with all of the current, very acceptable and traditional models that exist,” Kiersch said. “Similarly, there’s a variety of ‘products’ that are manufactured: There’s big budget, highly-visible blockbusters, and at the bottom of the scale there are the small films that are personal, and require far less of a staff.”

Not unlike the denizens of a grocery store, Kiersch finds that the appetite of the consumer varies. Yet he still finds that even at such an early stage, Oklahoma has the potential to satisfy both ends of the spectrum, with its relatively low-cost resources and welcoming business environment.

Despite the potential economic boon a successful industry can have on a state, many universities can’t afford to be particularly gung ho about such an endeavor. Kiersch’s current project, a low-residency screenwriting program, hopes to alleviate that concern.

Essentially, a screenwriting curriculum requires very little capital. A low-residency program provides students with less exposure to instructors, thus making the time spent with them significantly more valuable.

“In order to get something like this off of the ground, you need disciplines that enable students to work independently,” Kiersch said. “Things like photography, editing, and performing wouldn’t really work in that case.”

The true perseverance of a film curriculum on a national scale relies on an ability to cultivate media literacy. But the amount of information we consume via screens compared to how little the process is actually discussed in schools, most pressingly at an early level, is an issue.

“People are socially promoted to a level of study where they just fill a minimum role, and they’re undereducated because of the way funding works,” Kiersch said. “One thing we all commonly get, regardless of our status, is information through screens. Thus, we need to start educating in the process of media construction. We need to ask questions like, ‘Can the viewer discern the truth and make good choices?’”

He also finds that in pursuing such a curriculum, you ultimately uncover where you fit in culturally, religiously, and socially. At its core, media literacy can provide us with an avenue towards understanding one another. It is, essentially, the world’s language.

“I’ve seen how many people have poor grammatical skills, and thus can’t speak very well,” Kiersch said. “When they start working with film, though, they start to express themselves differently, as more educated and eager to learn. We can’t just be industry-centered; we have to learn how media literacy can help us communicate to the highest level of education. It’s where we gotta go.”