When he was 12, a “Stone Cold” Steve Austin T-shirt forever changed the way Eli Casiano saw himself in the world. His mom sometimes took in migrant Mexican laborers passing through their quiet town of Sulphur, Oklahoma while looking for work, and she suggested that Eli offer his shirt to one such traveler so that he would look more “American.” The idea was to blend in, to avoid suspicion. (What better way to blend in south-central Oklahoma, after all, than by sporting a tee emblazoned with a rattlesnake-wrapped human skull and a bold promise to “raise hell”?)

For all Casiano knows, this tremendously goofy piece of pro wrestling merchandise — signaling claim to that slippery abstraction of Americanness — might have saved that stranger’s life, or at least made his potentially dangerous passage less fraught. Either way, the exchange stuck with Casiano as an emblem of the two starkly different worlds he occupied as a third-generation Mexican-American in the heart of Arbuckle country. It’s a feeling that has followed him since childhood, and it’s part of what makes his exciting work as a visual artist so singularly disorienting and delightfully odd.

“Growing up, the Mexican kids thought I was rich because my dad worked at the hospital and I had a bike,” Casiano said.

I was sitting across from Casiano at a sleepy dive bar in Bloomington, Indiana, just west of the wooded campus of Indiana University. He planned to meet with IU’s art department faculty to discuss his upcoming MFA application. Outside, the snow was falling without ceremony as he talked candidly about the peculiar tension of being a brown face in a white place.

“I remember wanting to wear what I thought were ‘white people’ clothes — Tommy Hilfiger, or whatever,” he said. “I wanted to eat what they ate. It was a crazy jealousy I had towards [white] kids. And to them, I was always ‘not that kind of Mexican,’ if that makes sense. ‘White-Mexican.’ I didn’t talk with an accent, and my parents didn’t work at the egg farm or saddle shop.”

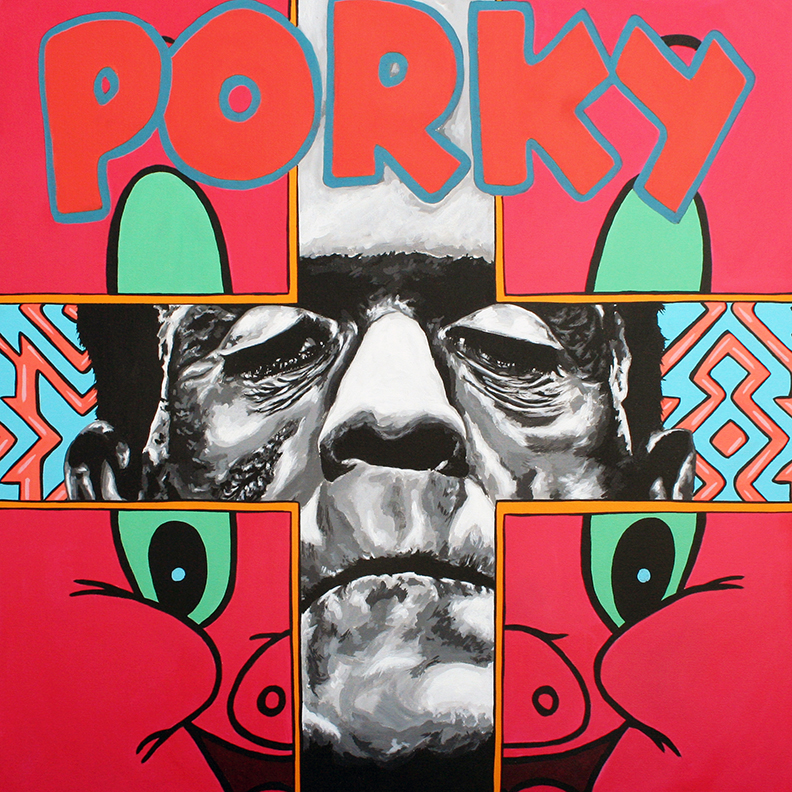

This feeling of displacement has electrified Casiano’s work, a funhouse-mirror world in which cultural identity is malleable and unfixed. In his 2014 painting “Fugazi,” a three-eyed Pinocchio stares pleadingly from under a Chinese dragon headpiece, his immaculate white-gloved hands gesturing toward the center of his face, where a snarling set of superimposed wolf teeth snap with real danger. Even more squarely playful works, like the psych-pop scrambler “Flawless Pig,” still get their mileage out of cultural and visual confusion. In that piece, “PORKY” is splashed in bubble letters across the top of the canvas, with a close-up rendering of the eponymous cartoon pig broken into large colorful squares in each corner of the painting. When I look at it, though, all I stubbornly see is the decidedly somber portrait of Frankenstein’s lonely monster filling the center gap, his eyes closed in quiet contemplation.

Works like these have been the cornerstone of Casiano’s young career, but he’s starting to get restless.

“I feel like I’m in an in-between stage with my art,” he said. “I’m getting tired of only working with acrylic paint, and I also don’t want to be known as ‘the guy that paints cartoons.’”

Casiano’s work got a much-needed jolt last summer when he attended the Drive-By Press Printmaking Workshop at the University of Oklahoma.

“That really encouraged me to get out of my comfort zone,” he said. “Working with new mediums has helped like I can’t even tell you. I started integrating sewing and printmaking into my compositions, and just generally rethinking my approach in a lot of ways. Beyond the workshop, just surrounding myself with printmakers has really changed the way I do things, especially relief and screen printers. Drive-By Press definitely gave me the itch to pursue an MFA, and it’s a big part of where I am right now.”

Casiano’s most visible moment came a few months before, when he was featured as a 2014 Momentum OKC Spotlight Artist. This distinction included a sizable grant from the Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition (OVAC), along with a prime spot in its yearly show featuring the best and boldest Oklahoma artists under 30. Casiano’s Momentum exhibit, End-in-Itself, was one of the his most fiendish and thrilling to date, replete with shrieking baboons in neon tribal garb, doe-eyed Disney characters painfully morphing into hideous technicolored monsters and other vivid abominations begging for their former dignity to be restored. Four nightmarish portraits hung around a suspended handmade speaker cabinet looping a dense, sample-based sound collage blasting somewhere between the jagged, power-tool drone of early Swans and the silky, sexed-up contours of ’90s radio R&B. There was no missing this thundering tumor hung near the entrance the Oklahoma City Farmers Public Market, and it made more than one passing patron visibly uncomfortable.

Of course, discomfort is Casiano’s bread and butter, and as the audio elements of his Momentum exhibit suggest, it goes beyond the world of visual art. In recent years, Casiano has been recording fun, filthy, head-scratching party rap under the moniker HOG. With songs like “A$$CLAP” and “Gas Station Beer,” his music traffics gleefully in scuzzy club-music tropes and fearless punk bravado.

“I’m trying to inhabit a character on stage,” he said. “I’ll snatch peoples’ drinks, or perform with my back to the crowd. I feel like the music sort of calls for that.”

He described his HOG persona as “a hedonistic freeloader who raps about women, money, and a social status that he doesn’t have. I think of him as a dude who only watches the Fast and Furious movies, but he also has a weird appreciation for Barbara Streisand and Liza Minnelli.” Armed with a keytar, a sampler, and a tallboy, HOG continues Casiano’s tradition of provocative misdirection, and of never quite belonging firmly in one camp.

“I thought, well, I like DJ Quick, and Frankie Knuckles, and Pantera. I should probably just smash them all together,” he said. “I like the food on my plate to touch. Maybe that’s where it comes from.”

While Casiano is dedicated to exploring these other avenues, visual art still consumes most of his attention. He has now submitted application materials to leading MFA programs all over the country, and the prospect of leaving the Sooner State spurs a complicated reflection on his recent years growing as an artist in Oklahoma City. He was just awarded another generous grant from OVAC, a vital supporter of his work, which will go toward his upcoming exhibit at the Campfire Gallery in San Francisco. Institutional champions aside, though, Casiano admitted that he hasn’t always felt entirely connected to the Oklahoma art scene.

“I mean, the community there is incredible. There’s always something going on, and a lot of really talented and dedicated people are involved in making that happen,” he said, pausing for a moment, studying the can of Schlitz he’s been nursing for the past half-hour. “But, I don’t know. I feel like I haven’t really found an audience to connect with. Sometimes it still feels foreign to me, I guess.”

This might deflate other artists, but I get the feeling that the never-quite-at-home sensation is part of what sustains Casiano’s creative spirit. Like “Stone Cold” Steve Austin, the patron saint of migrant Mexican laborers, I imagine Casiano emerging from spaces of alienation with beer-clutching fists held high in triumph. When I told him this, the snow outside the bar falling more steadily at the time, Casiano grinned and slammed back what was left of his Schlitz with the mock gusto of the Texas Rattlesnake himself. In a convincing approximation of Austin’s gravel-throated drawl, he crushed the can in his grip and buoyantly bellowed, “Oh, hell yeah!”